Recovery Collection: Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami 2011

Introduction

At 2:46pm on Friday, March 11, 2011, a Magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the northeast coast of Japan. This earthquake is the largest earthquake ever recorded in Japan, and the 4th largest earthquake recorded in the world. The earthquake caused a massive tsunami that devastated communities along Tohoku coastline, across many municipalities and multiple prefectures. The nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant ranked as the highest level 7 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES) of the International Atomic Energy Agency, making the 3.11 Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster a complex mega disaster with equally large and complicated challenges for recovery.

The damage from this complex disaster was widespread and devastating. As of June 2021, the official death toll includes 19,747 people who lost their lives in the tsunami[1], and 2,556 people whose remains were never found are listed as missing[2]. This includes 3,774 people who died later whose death have been official recognized as “indirect deaths”[3] caused by complications or other impacts of their experienced during and after the disasters. In the first few days after the disaster, more than 470,000 people evacuated from their homes, and in the following weeks, more than 350,000 continued living in long term evacuation.

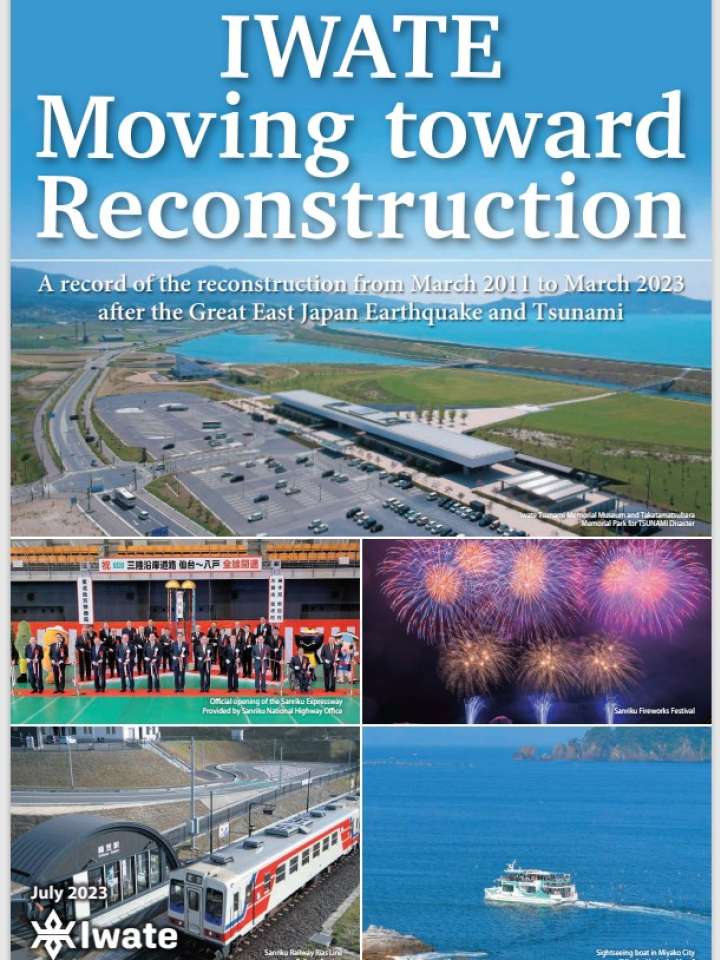

The tsunami affected areas of Tohoku include the jagged rias coastline of the Sanriku coast to the north, dotted with fishing communities where steep mountains meet the see. Sanriku coastcommunities have experienced large tsunamis every 30-40 years in the last century, including the 1896 Meiji Sanriku tsunami, the 1933 Showa Sanriku tsunami, and the tsunami that occurred after the 1960 Chile tsunami. Recovery after these historic tsunamis included rebuilding with partial or complete relocation of communities away from the ocean, but over generations, people moved back into many of these areas. Large tsunamis have occurred less frequently in history in the flat areas of the Sendai Plain, further south, but there are records in this area of the 1611 Keicho Tsunami, and experts consider that the GEJE is similar to the 869 Jogan tsunami.

Facing massive tsunami devastation that exceeded the expectations and expert predictions, recovery policy was shaped by the idea of reconstruction to reduce future tsunami risk, and especially the relocation of residential areas to higher elevations and/or inland locations. The government created a national Reconstruction Agency, and a menu of fully funded projects that municipalities could chose to include in reconstruction plans for their towns. Other new aspects of recovery after the GEJE included addition support for the private sector, such as the construction of temporary shopping arcades and subsidies for projects supporting groups of local businesses. In an area with many elderly residents, there were efforts to learn from previous disasters and provide support for the elderly, children, women, and psychosocial support in general. However, with the large scale of the disaster, affected area, and number of survivors, some problems already known from previous disasters, such as impacts of the loss of community and isolation were sadly experienced again.

Recovery after the nuclear disaster includes new challenges, for which there are no easy answers, including long-term displacement, uncertain futures, the loss of hometowns.

Japanese policies for post-disaster housing support include three clearly-defined phases, with distinct systems and responsibilities for funding and management. In the initial emergency phase, people stay in evacuation centers, often established in school gymnasiums or other large government own facilities. The provision of emergency temporary housing is carried out by the prefectural government. Since the 1995 Great Hanshin AwajiEarthquake in Kobe, all of Japan’s 47 prefectures had established contracts with the prefabricated builders association for their member companies to provide quickly provided prefabricated temporary housing in case of a large disaster. After the GEJE, there were more than 50,000 units of prefabricated temporary housing build for evacuees. Along with challenges to provide the needed numbers of temporary housing, combined with effective support for the promotion of local timber resources, there were also a large number of wooden temporary housing, especially those built by local contractors in Fukushima, which created more pleasant living environments for evacuees. In addition, the system of “designated temporary housing” in which the government pays for the rent of private apartment, was used for a large number of evacuees for the first time in Japan, for more than 70,000 households.

Policies supporting permanent housing recovery were similar to previous housing recovery projects in Japan, including the provision of Disaster Recovery Public Housing (government-subsidized rental housing) for disaster survivors, as well as provision of new residential lots provided for recovery.

[1] Japanese Reconstruction Agency 2021: https://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat1/sub-cat1-1/210601_genjyoutokadai.pdf

[2] Japanese Reconstruction Agency 2021: https://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat1/sub-cat1-1/210601_genjyoutokadai.pdf

[3] Japanese Reconstruction Agency 2021: https://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat2/sub-cat2-6/20210630_kanrenshi.pdf